Fresno’s Mason-Dixon Line

More than 50 years after redlining was outlawed, the legacy of discrimination can still be seen in California’s poorest large city.

James Helming knew every corner in Fresno. He knew which roads were paved and he knew which way the smoke from nearby factories blew. He knew the houses, and he knew who lived in them. It was his job, after all, to assess every neighborhood in the city for “desirability.” The year was 1936, and Helming, a junior field agent from a federal agency formed under the New Deal, was charged with making sense of Fresno's shifting demographics.

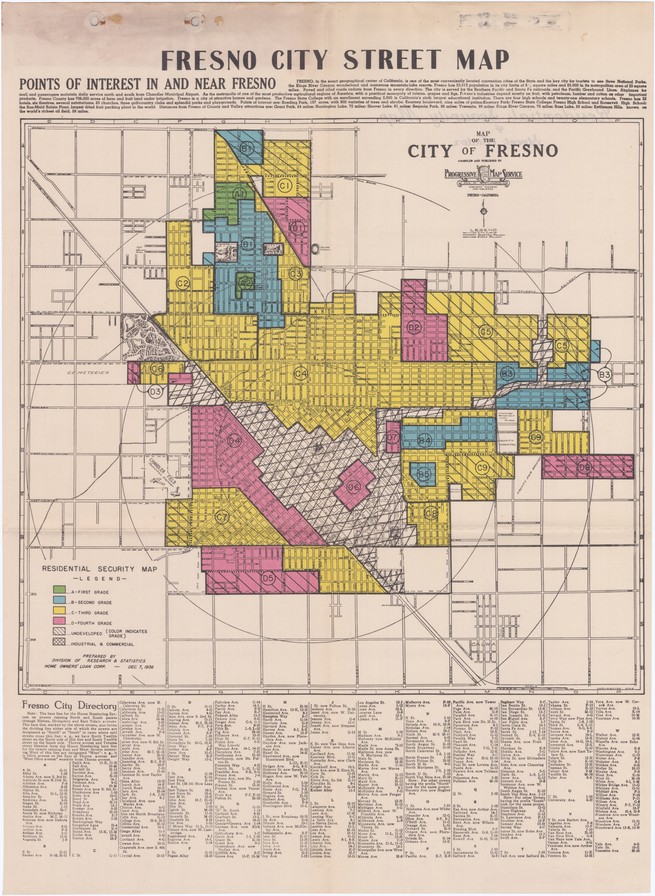

Armenian, Russian, and Italian residents were moving north, and the black and Hispanic populations were growing and expanding in their place. And Helming's agency, the Home Owners' Loan Corporation, drew color-coded maps to determine who would get the credit necessary to buy houses.

The Home Owners' Loan Corporation used this redlining map to preserve segregation in Fresno. The areas shaded red were home to an "undesirable" population. (Courtesy of T-RACES, University of Maryland)

White neighborhoods were shaded green, and white buyers in these areas were generally approved for loans. Neighborhoods with large minority populations were shaded red, denied mortgages, and labeled undesirable. Fresno’s west side was red, and in his report, Helming noted the “almost exclusive concentration of colored races” present there. He noted that in more affluent neighborhoods, like Fig Garden, “residence lots were sold under careful deed restrictions as to race.” If a neighborhood didn’t have these restrictions, Helming noted they were at risk of an “infiltration of a lower grade population.” These deed restrictions, known as racially restrictive covenants, were another mechanism that prevented people of color from buying homes in white neighborhoods. Helming’s report, one of more than 200 from cities across the country, reinforced residential segregation through a practice that came to be known as “redlining.”

Fresno is now the largest city in California’s Central Valley, the lifeblood of California, whose fertile fields feed the country. But in the majority-minority city of half a million, those riches are not equally divided. Eighty years after Helming published his report, the gulf between white, black, and brown residents remains embedded in the city’s geography. “Once you have a group of people segregated into a place you can take resources from that place,” said Amber Crowell, a Fresno State sociologist. “It creates a monster of social inequality that falls along racial lines, then it recreates itself. The boundaries are put in place and it automates itself from there.”

In the exclusive enclaves of north Fresno, life expectancy is 90 years. The neighborhoods are some of California’s richest, on par with parts of Silicon Valley and Beverly Hills. In the city’s south and southwest, Fresnans live, on average, 20 years less. There’s more concentrated poverty there than nearly anywhere else in America.

“We’ve done a very good job at sectioning off the poor,” said Matthew Jendian, chair of Fresno State’s sociology department. “We do that better than almost any other place in the country. And it’s not by accident.”

Segregation here is older than the city itself, dating to its post-Gold Rush-era founding.

Settled by homesteaders and land speculators, Fresno developed around a railroad station in a pattern so common in the rapidly industrializing country that it has since become a cliché: the poorest residents, and residents who were not white, were forced to live, literally, on the other side of the tracks. At an 1873 town meeting, Fresno’s white residents agreed not to rent, sell or lease any land east of the railroad tracks, where they and their families lived, to Chinese immigrants—many of whom built the very tracks that cut them off from the rest of Fresno.

This set in motion “the creation of a segregated ghetto that has lasted to the present day,” according to a paper by Ramón Chacón, a historian who grew up in west Fresno and researched racism and segregation in his hometown. Chacón, who died in 2017, wrote about the early, and often violent, segregation of the Chinese population to neighborhoods in southwest Fresno. In one essay, Chacón reported that, in 1893, white rioters chased 300 Chinese workers from Fresno farms back to the city’s Chinatown, using “blows and pistol shots.”

Over the next 25 years, the city grew quickly and attracted Mexican, Japanese, Armenian, and Italian immigrants, who were also forced to live in southwest Fresno. In 1918, a California state commission report titled “Fresno’s Immigration Problem” said that nearly all of the city’s “foreign born” lived in the “Foreign Quarter” on the west side. That same year, Fresno’s first-ever general plan formalized existing residential segregation by reserving the southern quadrants of the city for polluting, foul-smelling industrial businesses, and affordable housing. The zoning rules established a pattern that persists today: Fresno’s poorest and most vulnerable residents were consigned to the same neighborhoods as the city’s dirtiest factories.

These policies, and the redlining that cemented them, made it virtually impossible for black Americans, who came to Fresno in greater numbers after World War II, to move in anywhere but the city’s southwest. One report estimated that, by the 1950s, nearly 100 percent of black Fresnans lived on the west side. Another found that in 1960 Fresno had the highest degree of black-white segregation in California.

In the ‘50s, the construction of Highway 99, which today runs north and south through the Central Valley, created another physical barrier between the west side and the rest of Fresno and destroyed more than 20 blocks of existing housing. Later, at the height of the Cold War, a former member of the Fresno County Board of Supervisors would refer to Highway 99 and the railroad tracks as “Fresno’s Berlin Wall.”

The city’s schools were as divided as its neighborhoods. In 1973, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare found that Fresno Unified School District was in violation of the Civil Rights Act. Not only did the district have heavily segregated schools (Edison High School, in the city’s southwest, had a population that was 99.6 percent minority students) but school administrators were assigning black and Hispanic students to “mentally retarded classes,” Chacón found during the course of his research.

In the decades that followed, city plans and zoning ordinances kept the southwest isolated. Fresno’s leaders concentrated the city’s wealth and development farther north, catering to its affluent white neighborhoods. There, the city built shopping malls, hospitals and college campuses. The southwest got slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants. In Fresno, segregation that began with Chinese immigrants evolved over time to target Hispanic and, most explicitly and acutely, black residents.

The geographic, economic, and racial isolation of a city’s black and brown residents is a pattern duplicated across the country, said Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law, which details government policies that segregated U.S. neighborhoods.

“Fresno is no different than any other place in this respect,” Rothstein said in an interview. “You wouldn’t have the kinds of conflicts that existed in Ferguson or Baltimore, Milwaukee or St. Paul, or any of the hundreds of others over the years if you weren’t concentrating low-income young African American men in single neighborhoods where there’s little hope.”

Today, some argue that Shaw Avenue, an east-west thoroughfare that’s one of the city’s busiest, has replaced the railroad tracks as the city’s dividing line. White and wealthy above it, poor, black, and Hispanic below. A 1970s-era city planning document actually refers to the street as Fresno's Mason-Dixon Line.

There are exceptions, and pockets of prosperity and poverty exist above and below Shaw, but still, the side of the street a person lives on matters.

Margaret Katcher contributed to this report.